The Appalachian Region continues to experience higher rates of opioid misuse and overdose deaths than other parts of the country. While the impact of the burgeoning epidemic is being felt nationwide, states and counties within the Appalachian Region are particularly hard hit, with opioid overdose rates more than double national averages. Drawing on the research presented in the health disparities and Bright Spot reports, this brief:

- summarizes statistics on opioid misuse and overdose deaths in Appalachian communities,

- discusses key strategies and resources for addressing opioid misuse and overdose deaths, and

- provides recommendations for community leaders, funders, and policymakers.

This brief features promising practices, intervention strategies, and policy development and implementation ideas to reduce health disparities related to opioid misuse and overdose deaths.

This brief discusses five recommendations in detail:

- Prevent opioid misuse.

- Increase access to treatment for opioid use disorder.

- Implement harm reduction strategies to reduce the consequences of opioid use disorder.

- Support long-term recovery of opioid use disorder.

- Implement community-based solutions to prevent substance misuse.

Key Terms Used in this Brief:

- Opioid

- A class of pain-relieving drugs. Some opioids are illicit (e.g., heroin), while others are available by prescription (e.g., oxycodone).

- Heroin

- A highly addictive opioid drug derived from morphine.

- Opioid misuse

- Opioid misuse refers to 1) the use of prescription opioids without a prescription or in any way not directed by a clinician, or 2) the use of heroin. Opioid misuse can lead individuals to develop opioid use disorder.

- Opioid use disorder

- A problematic pattern of opioid use—typically prescription drugs or heroin—leading to clinically significant impairment or distress.

- Substance use disorder

- A medical condition in which one or more substances leads to clinically significant impairment or distress. Opioid use disorder is a type of substance use disorder.

Why Address Opioid Misuse in Appalachia?

Poisoning Mortality per 100,000, 2008-2014

Nationally, drug overdose deaths due to opioids have increased substantially since 1999.[6] In 2017, opioids were responsible for approximately 47,600 overdose deaths, or 67.8% of all overdose deaths.[7] Recent data indicate that the number of opioid-related deaths has now surpassed the number of deaths from motor vehicle accidents. Marked increases in opioid-related deaths have been cited as a key driver of decreasing life expectancy in the United States.[8]

These patterns are also evident in the Appalachian Region. Existing evidence suggests that residents of Appalachia are more likely to die prematurely than those who live outside of Appalachia. Among those living in Central Appalachia and in economically distressed counties, those differences are even greater.[9] While multiple factors contribute to decreasing life expectancy, notable trends in opioid-related deaths significantly contribute to the loss of life in Appalachia.[10]

The Creating a Culture of Health in Appalachia initiative has produced a series of detailed reports documenting key health challenges and opportunities in Appalachia. The Health Disparities in Appalachia report noted that poisoning mortality rates—which include poisoning from medication abuse, both pharmaceutical and illicit—were markedly higher (41.6%) in Appalachia than in the non-Appalachian United States. While not limited to opioid-related drug overdose deaths, findings from the initiative’s reports provide important context for understanding and addressing opioid misuse and overdose-related disparities by identifying factors that support a culture of health in Appalachian communities.

Opioid Misuse in Appalachia

Since 1999, opioid overdose deaths have increased more than four-fold in the United States—and the Appalachian Region has been disproportionately impacted. In 2017, four states within the Appalachian Region (West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky) had the highest rates of drug overdose deaths in the country. In addition, most Appalachian states experienced increases in drug overdose deaths between 2016 and 2017.

Data from a recent report documenting “diseases of despair” in Appalachia noted that overdose mortality rates are considerably higher in Appalachia than in the non-Appalachian United States.[11] The North Central and Central Appalachian subregions in particular experience poisoning mortality rates that are strikingly higher than what is observed outside the Appalachian Region.

Contributing Factors

Several factors contributing to higher rates of opioid misuse and overdose deaths converge in Appalachia. Higher rates of injury-prone employment, aggressive marketing of prescription pain medications to physicians, and an insufficient supply of behavioral and public health services targeting opioid misuse contribute to higher rates of opioid misuse and mortality in the Region.[12] These factors, coupled with limited access to treatment and high rates of poverty, create a multifaceted public health threat. Equally multifaceted intervention strategies are needed to address opioid misuse and overdose deaths in Appalachia.

Assessing Community Need for Prevention of Opioid Misuse and Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder

Conducting a Needs Assessment

Needs assessments are formative research activities that can help communities understand important cultural norms and attitudes that may affect efforts to reduce opioid use disorder and opioid overdoses. They can help community leaders, funders, and policymakers understand the prevalence and nature of the opioid problem in a particular community, including which populations are at a disproportionately high risk of developing an opioid use disorder. Conducting a needs assessment will also help leaders take stock of which programs and policies are already addressing opioid misuse and the extent to which they are working successfully.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provide a guide to how to conduct a community needs assessment that includes data sources and strategies.[13] Communities may also consider the following local sources of data:[14]

- Civic and non-profit organizations, for lists of current projects, more information about who and how many individuals are served, and plans for the future

- Community colleges/local universities, for academic research related to the community

- Faith-based groups, for membership numbers and community needs

- Health departments/healthcare providers, for local prevalence rates

- Libraries, for local history/information unique to the county

Quantitative data in conjunction with qualitative data from community forums and focus groups can help reveal how changes have occurred over time as well as current barriers to creating change. Identifying community assets is equally important to identifying challenges, and community leaders can take stock of existing resources systematically through asset mapping. Additional resources for conducting community needs assessments, including asset mapping, are provided at the end of this section.

Using State- and County-Level Data to Prioritize Resources

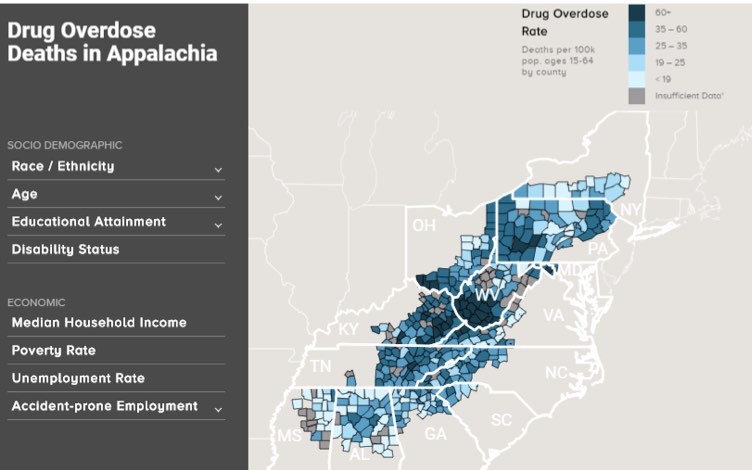

To target limited resources appropriately, community leaders, funders, and policymakers may consider leveraging county-level data to understand how the opioid crisis has impacted their community and to facilitate community planning. Several factors, including unemployment, poverty, disability, and age, influence high rates of opioid use and overdose in Appalachia. Assessing community needs will help program planners determine which of the recommendations presented in this brief have the greatest potential to reduce opioid overdoses. The Appalachian Overdose Mapping Tool can also help communities understand the impact of, and contributors to, the opioid epidemic in the Appalachian Region (see below).[15] Users can assess the overall drug overdose rate and the opioid overdose rate per 100,000 population in rural and urban Appalachian counties. Sociodemographic variables include race/ethnicity, age, educational attainment, and disability rates. Economic variables include median household income, poverty rate, unemployment rate, and accident-prone employment (e.g., manufacturing and construction). The Creating a Culture of Health in Appalachia initiative compiled data on 41 health indicators—including poisoning mortality—providing a comprehensive overview of health in the Appalachian Region.

Practical Strategies and Recommendations

Preventing and treating opioid use disorder in Appalachia could help decrease the number of opioid overdose deaths in the Region. In this section, we present policies, programs, and initiatives that show promise or have successfully reduced opioid misuse and/or overdose. We also provide examples of intervention strategies taking place in Appalachia.

While this issue brief focuses on opioids, Appalachian communities are also facing high rates of other forms of substance use disorder. As described in the Health Disparities Related to Smoking in Appalachia issue brief, approximately 20% of Appalachian adults report being smokers, compared to 16% of adults in the non-Appalachian United States. Appalachian residents also have higher rates of alcoholic liver disease/cirrhosis than non-Appalachians, which is a consequence of alcohol use disorder.[16] Appalachian communities whose members experience other forms of substance use disorder may also benefit from the recommendations presented in this issue brief, because opioid misuse may co-occur with misuse of other substances. For example, one study of two rural Appalachian counties found that current users of benzodiazepines were significantly more likely to misuse prescription opioids and use other illicit drugs, including cocaine.[17]

Recommendations for reducing opioid misuse and overdose disparities include the following:

- Prevent opioid misuse.

- Increase access to treatment for opioid use disorder.

- Implement harm reduction strategies to reduce the consequences of opioid use disorder.

- Support long-term recovery of opioid use disorder.

- Implement community-based solutions to effect change.

Recommendation #1: Prevent Opioid Misuse

Overprescribing opioids can lead to increased diversion of unused pills for opioid misuse and increased rates of opioid use disorder. The Appalachian Region has experienced historically high rates of opioid prescribing compared to other regions in the United States.[18] In 2016, congressional districts with the highest rates of opioid prescribing were concentrated in Appalachia, the South, and the rural West.[19]

Community-Based Strategies

Engage Youth to Prevent Initiation of Opioid Use

The U.S. Department of Education recommends educating students and their families about the risks of opioid misuse and ways to prevent youth from developing opioid use disorder.[20] The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Institute of Medicine describes three types of prevention interventions that address mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders.[21] First, universal interventions are typically low-cost programs that serve a whole population, regardless of individual-level risk. These could include school-based or community-based interventions that teach youth skills to resist substance use. For example, in Grant County, West Virginia, a Bright Spot case study community, schools are implementing the Too Good for Drugs and Students Against Destructive Decisions programs to prevent substance misuse among students.[22] In McCreary County, Kentucky, another Bright Spot case study community, the Adanta Regional Prevention Center works with local school staff to implement evidence-based programs to prevent substance use disorder. Many communities are also implementing Communities That Care (CTC), a prevention system that empowers coalitions to identify protective and risk factors that affect behavioral issues among youth. CTC guides communities through implementation of effective interventions to address the identified needs of youth, including illicit substance use.

Second, selective interventions target youth who are at higher risk for developing substance use disorder. For example, West Virginia’s Handle with Care program is a collaboration between schools, law enforcement, and health providers that helps students access resources and support after they undergo a traumatic event, such as a parent’s overdose. Third, indicated interventions help prevent students who exhibit early substance misuse or other risky behaviors from developing substance use disorder.

Increase Use of Data from Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs)

PDMPs are statewide databases that track prescriptions of controlled substances. The utilization of PDMPs can help decrease overprescribing by allowing providers to identify patients who are obtaining prescriptions for opioids from multiple providers. Public health agencies can also use data from PDMPs as surveillance tools to track trends in opioid prescribing. Recommendations for effective PDMPs include ensuring that data from PDMPs is easily accessible to clinicians and integrated into clinical workflows.[23] One approach to improving accessibility involves integrating PDMP data into electronic health records (EHRs) and health information exchanges. In 2018, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services invested in an integration platform that allows clinicians to easily access PDMP data through EHRs.[24] Kentucky’s “gold standard” PDMP mandates that all providers and pharmacists register with the database and requires timely data reporting.[25] The Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Training and Technical Assistance Center at Brandeis University has also developed additional best practices for PDMP enhancement.

Increase Adherence to Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

Lack of clarity about the appropriate use and dosing of prescription opioids can contribute to overprescribing. In 2016, the CDC released guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain in an effort to provide recommendations about initiating opioid treatments, selecting the appropriate formulation and dose, and assessing risks of opioid use.[26] States and communities are taking steps to ensure that providers are aware of and adhere to the evidence-based guidelines. For example, Tennessee enacted new opioid prescribing laws in 2018 that reflect these guidelines.[27]

Communities may also seek to implement health information technology strategies in order to improve adherence to prescribing guidelines. Integrating clinical decision support tools into EHRs can help improve the ability of primary care providers to follow guidelines and decrease the number of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy.[28] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also developed a mobile application to provide easy access to prescribing guidance, training for motivational interviews, and calculating total daily opioid doses.[29]

Additional Resources for Preventing Opioid Misuse

Engage youth to prevent initiation of opioids

- The U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Science manages a Regional Education Laboratory in Appalachia that discusses the intersection of opioid misuse and student trauma.

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s Evidence-Based Practices Resource Center offers a wealth of prevention resources focused on children and youth.

- The Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development, an evidence-based program registry hosted by the University of Colorado Boulder and funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, includes descriptions of programs that have been effective at preventing illicit drug use among children and teens.

Increase use of data from PDMPs

- The PDMP Training and Technical Assistance Center at Brandeis University offers a comprehensive collection of resources and best practices for PDMPs.

- The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials offers a compendium of resources to Improve Monitoring and Surveillance for substance misuse through PDMPs, including considerations for policymakers and providers.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts developed Evidence-Based PDMP Practices to Increase Prescriber Utilization, which include case studies from states in the Appalachian Region such as Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio.

Increase adherence to opioid prescribing guidelines

- The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain gives recommendations for when to prescribe opioids for chronic pain and how to address the risks and potential consequences of opioid use. Clinical tools can help providers adhere to the guidelines.

- SAMHSA offers additional information about earning continuing medical education credits for Opioid Prescribing Courses for Health Care Providers.

Recommendation #2: Increase Access to Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder

Community-Based Strategies

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is an evidence-based intervention that combines U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications with counseling or behavioral therapy to treat opioid use disorder and help sustain long-term recovery from opioid addiction.[30] The three drugs that are approved by the FDA for treatment of opioid use disorder are methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Methadone must be dispensed in licensed opioid treatment centers, while naltrexone and buprenorphine can be prescribed by waivered physicians in office settings. The FDA recommends access to all three treatments, with the physician deciding which one to prescribe based on their assessment of the severity of the individual’s opioid use disorder and needs. Despite strong evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of MAT in treating opioid use disorders, access and coverage remain limited in Appalachia. For example, state Medicaid programs in Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia do not cover methadone treatment.[31] To improve access to MAT, communities may seek to increase the number of providers who offer MAT, invest in telehealth programs, and integrate behavioral health into primary care and emergency department settings.

Increase the Number of Providers Offering MAT

According to the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000), physicians who complete an eight-hour training course can apply for a waiver from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency to prescribe buprenorphine. Key barriers to increased access to buprenorphine treatment include lack of provider experience with MAT and with managing patients with opioid use disorder.[32] One strategy to increase the number of providers engaging in MAT is Project ECHO, an evidence-based telementoring intervention that pairs rural providers with behavioral health specialists through videoconferencing.[33] Substance use specialists can review specific case studies and offer didactic presentations on topics related to MAT, which builds the capacity of rural providers to manage treatment for their patients. For example, the West Virginia Project ECHO Medication-Assisted Treatment has covered the use of naltrexone and buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid use disorders. [34] The Ohio Opiate Project ECHO also offers mentoring to newly waivered physicians in order to increase their comfort with prescribing buprenorphine.[35]

Invest in Telehealth Programs

Telehealth can help overcome provider shortages and limited access to opioid treatment programs by virtually connecting patients with substance use specialists. Providers can connect with a qualified physician to secure a buprenorphine prescription for a patient. Patients can also receive counseling services via video teleconference. For example, the Comprehensive Opioid Addiction Treatment (COAT) program combines MAT with group psychotherapy, individual therapy, and participation in weekly community support programs.[36] Patients who live in rural communities with limited access to local behavioral health providers meet with a psychiatrist through telehealth to receive assessment and referral to COAT. An evaluation of the program found similar rates of abstinence and retention between groups that experienced group therapy MAT services in-person and through telepsychiatry.[37]

Integrate Behavioral Health Treatment in Primary Care Settings and Emergency Departments

States and communities are expanding access to MAT beyond specialized treatment facilities, which can have long waitlists and limited capacity to meet the demand of people seeking treatment for opioid use disorder. One effective approach to increasing access to MAT is integrating behavioral health into primary care, where people with opioid use disorder can receive care in their communities. The evidence-based hub-and-spoke model in Vermont pairs opioid treatment programs (hubs) with waivered providers at primary care practices, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and other facilities throughout the state (spokes).[38] The spoke MAT team—consisting of lead provider, nurse, and licensed counselor— receives consultations and training from the hubs in order to develop treatment plans and manage patients. The hub-and-spoke system has been effective in increasing the state’s capacity to treat opioid use disorder: Vermont had the greatest number of people in treatment per 1,000 people among all states in 2017.[39]

Communities are also integrating access to MAT in emergency departments in an effort to immediately link patients to care. Ohio is facilitating MAT in emergency departments in order to quickly link patients who might otherwise experience long waitlists for office-based treatment to care.[40] Patients flow from induction of MAT in the emergency department to interim care by a primary care physician, after which they transition to care in office-based opioid treatment or an opioid treatment program. The Potomac Highlands Guild in Grant County, West Virginia—a Bright Spot case study community—is also facilitating connections between the emergency department and intensive outpatient treatment for substance use disorder.[41] Staff provide round-the-clock support to the local emergency department for any crisis related to substance use disorders.[42]

Both primary care practices and emergency departments are also using screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) to identify patients who need support for opioid use disorder. SBIRT is an evidence-based model that involves screening patients for substance use disorder, providing a brief intervention to educate patients about their substance use, and referral to treatment and additional services. SBIRT can help provide early intervention services for people with opioid use disorder before they experience more severe consequences, including overdose. Research suggests that SBIRT for opioid dependence can be more effective if patients also receive an initial dose of buprenorphine/naloxone until they receive follow-up care.[43] The West Virginia SBIRT Project is increasing the use of SBIRT in rural community-based primary health care clinics, emergency departments, and school-based health clinics, and connecting patients who need further care to community-based behavioral health centers that offer interventions tailored to Appalachian culture and values.[44]

Additional Resources for Increasing Access to Treatment

Increase the number of MAT providers

- SAMHSA offers information about Buprenorphine Training for Physicians and other training materials and resources for MAT.

- The Providers Clinical Support System, funded by SAMHSA, offers information and resources for providers seeking to obtain a waiver for prescribing buprenorphine.

Invest in telehealth programs

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has released a brief to clarify regulations for Telemedicine and Prescribing Buprenorphine for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder.

- The SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions’ Telebehavioral Health Training and Technical Assistance Series provides information about planning for and implementing telehealth programs that address behavioral health.

Integrate behavioral health treatment in primary care settings and emergency departments

- The SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions developed a paper to provide guidance for communities seeking to integrate MAT into safety-net settings. The center also provides SBIRT resources, including educational courses and implementation supports.

- The Kentuckiana Health Collaborative’s SBIRT Toolkit for Addressing Unhealthy Substance Use in Primary Care Settings focuses on educating providers about implementing SBIRT to address opioid misuse.

Recommendation #3: Implement Strategies to Reduce the Harmful Consequences of Opioid Use Disorder

Opioid use disorder can have severe health, social, and economic consequences for people with the disorder and their families. Communities are implementing several strategies to reduce the harm associated with opioid use disorder, including overdose and transmission of blood-borne infections such as HIV and viral hepatitis. Several of these approaches are included in the CDC’s Evidence-Based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States.

Policy-Based Strategies

Expand Naloxone Programs

Naloxone is a medication used to rapidly reverse opioid overdoses. Certain formulations of naloxone can be administered by anyone who has received training, including emergency medical services (EMS), other first responders, and community members. Efforts to expand access to and use of naloxone often focus on offering training that identifies the signs and symptoms of an opioid overdose and how to administer naloxone to reverse it.[45] Research demonstrates decreased rates of opioid overdose deaths in communities that received overdose education and naloxone distribution training compared to communities that did not undergo training.[46] Many programs in Appalachia are implementing training programs in order to decrease opioid-related overdoses. For example, Full Circle Recovery Center in Franklin, North Carolina, worked with EMS, law enforcement, and other first responders to provide tailored education about opioid use disorder and naloxone administration.[47] Project REVIVE in Southwest Virginia provides free community training and naloxone response kits to increase the ability of lay rescuers to reverse opioid overdoses. [48]

Implementing coprescription of naloxone can also effectively reduce opioid-related overdoses.[49] HHS recommends that clinicians consider coprescribing naloxone to patients who are prescribed opioids and at risk of an overdose, including those who are taking large doses or have a co-occurring substance use disorder.[50] HHS also recommends that clinicians prescribe naloxone to patients at risk of an opioid overdose, including those who are using illicit opioids or receiving treatment for opioid use disorder.

Other strategies to improve access to and use of naloxone include providing immunity from criminal prosecution, civil liability, and professional sanctions to prescribers and dispensers for distributing naloxone to a layperson. Many states also allow for standing orders for naloxone, which allow prescribers to authorize pharmacies to distribute naloxone to eligible individuals without a prescription. Appalachian communities should be aware of state and local laws that affect the ability of community members to access and administer naloxone. The Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System provides a map of naloxone laws that were enacted before July 1, 2017.

Promote the Use of Drug Courts

Drug courts aim to keep people who are recovering from opioid use disorder out of the criminal justice system. Participation in drug courts is often a condition of pretrial release programs, wherein individuals must complete a behavioral health treatment plan in order to avoid incarceration. Drug court models typically involve a screening process to identify risks and needs, periodic interaction with a judge, regular monitoring and supervision, incentives and sanctions based on the participant’s progress, and access to recovery services.[51] Many communities in the Appalachian Region are implementing drug courts:

- As profiled in the Bright Spot case studies report, Potter County, Pennsylvania, is implementing a pretrial diversion program and specialty drug courts to link people with substance use disorder to treatment.[52] These programs have contributed to decreased recidivism, increased cost savings, and improved opportunities for community members to achieve long-term recovery.

- In Appalachian Tennessee, the 4th Judicial District’s Recovery Oriented Compliance Strategy (TN ROCS) offers a pathway to treatment for offenders who have substance use disorders and are considered low-risk for recidivism. TN ROCS participants meet with criminal justice liaisons to receive behavioral health screenings, corrections officers to complete regular check-ins, and the district judge to provide updates on their progress. Key successes have included prevention of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) among infants born to pregnant women participating in TN ROCS.

- Some Appalachian communities are implementing specialized Family Treatment Drug Courts that also involve child welfare services, with the ultimate goal of promoting safe and healthy environments for children. For example, the Tompkins County Family Treatment Court connects parents who have substance use disorder with treatment and parenting classes. The program has been successful in reducing the amount of time in foster care placement among children of parents with substance use disorder.

Community-Based Strategies

Implement Syringe Services

Syringe services programs (SSPs) offer sterile syringes and safe syringe disposal sites to people who inject drugs. SSPs are effective in reducing the spread of HIV and viral hepatitis.[53] Comprehensive SSPs also provide linkages to care and other resources in order to treat opioid use disorder and offer early interventions for health complications.[54] For example, programs could also refer clients to MAT and behavioral therapy, naloxone training, prenatal and women’s health resources, and screening for HIV and hepatitis C and B. Access to SSPs has grown in some Appalachian states that have been heavily affected by the opioid epidemic. From 2013 to 2017, the number of SSPs in Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia has grown from 1 (in West Virginia) to 53 across the 3 states. Many of these SSPs are located in Appalachian eastern Kentucky and western North Carolina.[55],[56] For example, the Olive Branch Ministry in Appalachian North Carolina operates a mobile SSP that provides clean syringes and refers individuals to treatment and peer support services. Other Appalachian SSPs include the LENOWISCO Harm Reduction Program in Virginia, which provides referrals to social services and medical care; pre-exposure prophylaxis; non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis for people at risk of contracting HIV; counseling; and other services in addition to syringe exchanges.[57]

Implement Safe Drug Disposal Programs

Safe drug disposal programs allow people to anonymously dispose of expired and unused prescription opioids in order to prevent misuse and diversion. One study found that permanent drug donation box collections in Appalachian Tennessee were effective in removing controlled substances from communities.[58] Communities may work with law enforcement to implement permanent donation boxes in locations that are accessible and convenient, including pharmacies, medical facilities, local police departments, and other locations. For example, Wirt County, West Virginia—a Bright Spot case study community—has a permanent receptacle in front of the courthouse that allows community members to drop off medications and other substances.[59] The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration also encourages National Prescription Drug Take-Back Day events in order to promote safe disposal of drugs. [60] A study of 11 drug take-back events in Appalachian Tennessee and Virginia collected almost 17,000 containers of medications from 752 participants.[61]

Prevent and Treat Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) occurs when newborns who were exposed to substances in the womb experience withdrawal symptoms after birth.[62] While long-term effects of opioid withdrawal on the newborn brain are poorly understood, short-term symptoms include excessive crying, irritability, fever, hyperactivity, poor feeding, sleep problems, and slow weight gain, among others.[63] Many communities in Appalachia have experienced growing rates of NAS as a result of the opioid crisis. For example, cases of NAS tripled in Kentucky from 2008 and 2014, and the rate of NAS in Appalachian counties was double that of non-Appalachian counties.[64] The CDC recommends that clinicians discuss the risks of NAS before prescribing opioids to pregnant women and suggests increasing access to family planning resources for women who use opioids.[65] Some Appalachian communities are also involving public health and social service agencies in efforts to prevent NAS. For example, the Sullivan County Regional Health Department in Appalachian Tennessee is providing educational sessions on NAS prevention and referring eligible women to home visiting programs. Appalachian communities are also working with payers to seek reimbursement for NAS treatment. In 2018, West Virginia became the first state to receive Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approval to offer NAS treatment services.

Additional Resources for Implementing Harm Reduction Strategies

Expand naloxone programs

- HHS released guidelines for coprescribing naloxone to patients at high risk for an opioid overdose to help providers understand which patients could benefit from receiving a naloxone prescription.

- SAMHSA developed a fact sheet that describes resources for first responders and others that are preparing to distribute naloxone.

Promote the use of drug courts

- SAMHSA’s brief, Adult Drug Courts and Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Dependence, educates drug court personnel about MAT.

Implement syringe services and proper drug disposal programs

- The Harm Reduction Coalition developed the Guide to Developing and Managing Syringe Access Programs to provide a comprehensive overview of the process of implementing an SSP.

- CDC’s Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) Developing, Implementing, and Monitoring Programs fact sheet offers a compendium of resources for communities seeking to implement an SSP with a comprehensive prevention approach.

Implement safe drug disposal programs

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration offers information, resources, and frequently asked questions about disposal of unused medicines.

Prevent and treat NAS

- The National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare provides links to publications, webinars, videos, and research studies focused on NAS.

Recommendation #4: Support Long-Term Recovery from Opioid Use Disorder

Policy- and Community-Based Strategies

Address Upstream Factors That Affect Long-Term Recovery

The root causes of opioid use disorder are influenced by larger social, economic, and environmental factors. These social determinants of health also affect the ability of individuals to access treatment and to address risk factors that pose challenges to long-term recovery. The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis released recommendations that address the social and environmental context of opioid misuse. Policy-based recommendations include implementing reimbursement for recovery support services for job training and supportive housing, allowing individuals with felony convictions to apply for business and occupational licenses, and promoting cross-agency collaboration to support the development of recovery residences. Community-based recommendations include implementing family-centered treatment programs, supporting sober housing programs on college campuses, and developing best practices for employers about hiring and supporting employees with substance use disorder.

Community-Based Strategies

Promote the Use of Peer Recovery Programs

Individuals and their families may require additional support in the process of recovering from opioid use disorder. Effective strategies to extend support include peer recovery programs[66] that involve people in long-term recovery from substance use disorder—sometimes called peer support specialists or peer recovery coaches—who can share their experiences with those in similar circumstances. In addition to providing mentorship, peer support workers can help individuals navigate court systems, connect to community resources, and build healthy social networks. For example, the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services funds the Lifeline Peer Project, in which peer support representatives start self-help support groups for youth and adults in recovery.[67] Sequatchie County, Tennessee, a Bright Spot case study community, implemented Project Lifeline to address stigma related to addiction and build community support for policies that provide treatment and recovery services.

Additional Resources for Supporting Long-Term Recovery

Address upstream factors that affect long-term recovery

- The Center for Health Policy at the Brookings Institution and the University of Southern California’s Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics collaborated on a report, Un-burying the Lead: Public Health Tools Are the Key to Beating the Opioid Epidemic, which describes the importance of addressing social and environmental risk factors for opioid misuse.

Promote the use of peer recovery programs

- SAMHSA offers Peer Support Resources that provide additional information about the role of peers in the recovery process for substance use disorders.

Recommendation #5: Implement Community-Based Solutions to Prevent Substance Misuse

Many communities are creating formal coalitions to strengthen partnerships between multiple sectors affected by substance use disorders, including law enforcement, social service providers, schools, health providers, and policymakers. Community coalitions can affect change at the systems level and promote upstream interventions to prevent opioid misuse. Several communities in Appalachia have established coalitions that are addressing the opioid crisis:

- The Madison Substance Awareness Coalition in North Carolina brings together a broad range of community partners—representatives from law enforcement, schools, public health agencies, health care providers, social services, pharmacies, and faith-based organizations—to reduce misuse of opioids. As profiled in the Bright Spot case studies report, coalition members provide community education about prescription medication misuse, train community members on the use of naloxone, and distribute lock boxes to promote safe medication disposal.

- The Coffee County Anti-Drug Coalition in Tennessee developed the Count It! Lock It! Drop It!® model to prevent diversion of prescription medications. The program educates patients about counting their pills, locking their medication, and disposing of unused medications in safe locations or at take-back events. Several community partners are involved in Count It! Lock It! Drop It!®, including law enforcement offices and pharmacies that host drop boxes.

- The Tioga County Allies in Substance Abuse Prevention (ASAP) coalition in New York, profiled in the Bright Spot case studies report, includes representatives from local school districts, nonprofits, parents, and other community members.[68] ASAP focuses on preventing substance use disorder among youth by facilitating panel discussions, conducting needs assessments, disseminating messaging about substance use, and creating positive leadership and social opportunities for youth.

- The Prevention, Intervention, Treatment, Anti-Stigma and Recovery (PITAR) coalition in Grant County, West Virginia, profiled in the Bright Spot case studies report, brings together representatives from the prosecutor’s office, sheriff’s department, drug court, and treatment centers to discuss solutions to the opioid epidemic.

Additional Resources for Implementing Community-Based Solutions

- The Rural Health Information Hub describes program models and considerations for community coalition models.

- The Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America’s National Community Anti-Drug Coalition Institute developed a Handbook for Community Anti-Drug Coalitions that reviews frameworks and offers recommendations for establishing an effective coalition.

- The Appalachian Regional Commission released a report, Communicating about Opioids in Appalachia: Challenges, Opportunities, and Best Practices, which can help community-based organizations in Appalachia identify effective messaging to support opioid misuse prevention and recovery.

Strategies and Recommendations for Funders

Funders throughout the Region have the opportunity to invest in initiatives and activities that help prevent and reduce opioid use and overdose deaths across Appalachia. Below, we describe strategies for funders seeking to reduce opioid-related health disparities in the Appalachian Region.

Leverage existing assets

Funders can leverage existing programs, practices, and policies by promoting the replication and adoption of successful programs and strategies. Appalachian communities have many assets that should be recognized and promoted. Community members are often connected through volunteering and coalition building. They also build strong social connections through faith- and community-based organizations, schools, local businesses, and shared culture and history. Funders can continue to support or increase funding for coalitions that are implementing community-based strategies to address substance use disorder. Funders can also support existing community or statewide efforts to address the opioid crisis, such as take-back events.

Strengthen community implementation capacity

Funders can strengthen community implementation capacity in Appalachian communities. Opportunities to increase capacity include (1) enhancing individual-level knowledge and skills that facilitate community action, and (2) fostering organizational and systems-level capacity. Examples of organizational and systems-level capacity include engaging in community visioning and strategic planning, building networks and engaging community stakeholders, writing grants, and engaging in local and regional policy advocacy, among others. Funders can consider working with community-based organizations to strengthen their capacity to assess community needs, identify evidence-based or promising interventions, and implement programs that address substance use disorder.

Focus on cross-sector collaboration through philanthropic strategies

Funders can facilitate collaboration between community members, the public, and private-sector individuals, which is critical to addressing opioid misuse within the Region. Through a coordinated use of resources, leadership, and action, communities can work together towards a common goal, using multiple perspectives and different areas of expertise. Government, the health care system, schools, private businesses, and community organizations all have critical roles in this effort. A key strategy to support cross-sector collaboration is to fund community coalitions that focus on preventing substance misuse and treating substance use disorder. For example, 32 anti-drug UNITE coalitions receive funding from the Kentucky legislature and private donors to implement local solutions to substance misuse in Appalachian Kentucky.

Build the Appalachian evidence base

The Bright Spot case studies report identified examples of promising practices to address opioid misuse in Appalachian communities. However, these programs and their outcomes are often not well documented. For long-term changes to occur, successful programs need to be evaluated rigorously and shared widely. Funders should encourage evaluation among their grantees to ensure program effectiveness is measured and documented. Evaluation, along with increased efforts to document local successes, will provide a more robust evidence base for Appalachian-specific programs and policies to address opioid misuse. The Rural Health Information Hub, supported by HRSA, provides additional information about effective and promising models and innovations in the area of substance misuse, including examples from the Appalachian Region.

References

[1] National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Opioids. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids.

[2] National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018, June). What is heroin and how is it used? Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/heroin/what-heroin.

[3] Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). Results from the 2016 national survey on drug use and health: Detailed tables (p. 2889). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Commonly used terms. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/terms.html.

[5] MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (2018, March 26). Substance use disorder. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001522.htm.

[6] National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2019). Overdose death rates. Retrieved from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

[7] Seth, P., Scholl, L., Rudd, R. A., & Bacon, S. (2018). Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants – United States, 2015–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(12), 349-358. doi:10.1111/ajt.14905.

[8] Ho, J. Y., & Hendi A. S. (2018). Recent trends in life expectancy across high income countries: Retrospective observational study. BMJ, 362. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2562.

[9] Appalachian Regional Commission. (2015). Health disparities in Appalachia. Retrieved from: https://www.arc.gov/research/researchreportdetails.asp?REPORT_ID=138.

[10] Scholl, L., Seth, P., Kariisa, M., Wilson, N., & Baldwin, G. (2019). Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2013–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(51-52), 1419-1427.

[11] Meit, M., Heffernan, M., Tanenbaum, E., & Hoffmann, T. (2017). Appalachian diseases of despair. Retrieved from: https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/AppalachianDiseasesofDespairAugust2017.pdf.

[12] Moody, L. N., Satterwhite, E., & Bickel, W. K. (2017). Substance use in rural Central Appalachia: Current status and treatment considerations. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 41(2), 123.

[13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Participant workbook: Community needs assessment. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fetp/training_modules/15/community-needs_pw_final_9252013.pdf.

[14] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Division of Public Health. (2014). Community health assessment guide book. Retrieved from: https://publichealth.nc.gov/lhd/docs/cha/Archived-CHA-Guidebook.pdf.

[15] NORC at the University of Chicago. (2017). Appalachian overdose mapping tool. Retrieved from: https://overdosemappingtool.norc.org/.

[16] Meit et al., 2017.

[17] Havens, J. R., Walker, R., & Leukefeld, C. G. (2010, September). Benzodiazepine use among rural prescription opioids users in a community-based study. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 4(3), 137–139.

[18] Moody, L. N., Satterwhite, E., & Bickel, W. K. (2017). Substance use in rural Central Appalachia: Current status and treatment considerations. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 41(2), 123.

[19] Rolheiser, L., Cordes, J., & Subramanian, S. V. (2018, September 1). Opioid prescribing rates by congressional districts, United States, 2016. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1214-1219.

[20] U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Combating the opioid crisis: Schools, students, families. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.ed.gov/opioids.

[21] National Research Council and Institute of Medicine Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse among Children, Youth, and Young Adults. (2009). Research advances and promising interventions. In M. E. O’Connell, T. Boat, & K. E. Warner (Eds.), Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32789/.

[22] Creating a culture of health in Appalachia: Exploring bright spots in Appalachian health: Case Studies.

[23] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). What states need to know about PDMPs. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/states.html.

[24] EHR Intelligence. (2018). NC department of health: Enabling EHR integration of PDMP data. Retrieved from: https://ehrintelligence.com/news/nc-department-of-health-enabling-ehr-integration-of-pdmp-data.

[25] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Kentucky meets gold standard for prescription drug monitoring programs. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/capt/tools-learning-resources/kentucky-meets-gold-standard-prescription-drug-monitoring-programs.

[26] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). CDC guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fmmwr%2Fvolumes%2F65%2Frr%2Frr6501e1er.htm.

[27] Tennessee Medical Association. (2018). Tennessee opioid prescribing law. Retrieved from: https://www.tnmed.org/TMA/Member_Resources/Opioid_Resource_Center.

[28] Anderson, D., Zlateva, I., Khatri, K., & Ciaburri, N. (2015). Using health information technology to improve adherence to opioid prescribing guidelines in primary care. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(6), 573–579. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000177.

[29] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). CDC opioid prescribing guideline mobile app. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/App_Opioid_Prescribing_Guideline-a.pdf.

[30] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Medication assisted treatment. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment.

[31] The Foundation for AIDs Research. (n.d.). Opioid and health indicators database. Retrieved from: http://opioid.amfar.org.

[32] Andrilla, C. H. A., Moore, T. E., & Patterson, D. G. (2019). Overcoming barriers to prescribing buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder: Recommendations from rural physicians. The Journal of Rural Health, 35(1), 113-121.

[33] Project Echo. (2018). Research. Retrieved from: https://echo.unm.edu/about-echo-2/research/.

[34] West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute. (2017). WV project ECHO medication-assisted treatment. Retrieved from: wvctsi.org/programs/community-engagement-outreach/project-echo/wv-project-echo-medication-assisted-treatment/.

[35] Ohio Mental Health and Addiction Services. (2019). Ohio opiate project ECHO: Expanding access to medication assisted treatment. Retrieved from: https://workforce.mha.ohio.gov/Workforce-Development/Health-Professionals/Opiate-Project-ECHO-CMEs.

[36] West Virginia University. (2019). Comprehensive opioid addiction treatment providers group-based treatment program using medication assisted therapy. Retrieved from: https://www.hsc.wvu.edu/substance-abuse-prevention/patient-care-initiatives/comprehensive-opioid-addiction-treatment-provides-group-based-treatment-program-using-medication-assisted-therapy-mat/.

[37] Zheng, W., Nickasch, M., Lander, L., Wen, S., Xiao, M., Marshalek, P., Dix, E., et al. (2017). Treatment outcome comparison between telepsychiatry and face-to-face buprenorphine medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder: A 2-year retrospective data analysis. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11(2), 138-144.

[38] University of Vermont Center on Behavior and Health. (2017). ADAP hub and spoke evaluation. Retrieved from: http://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADAP_Hub_and_Spoke_Evaluation_2017_1.pdf.

[39] Brooklyn, J. R., & Sigmon, S. C. (2017). Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: Development, implementation, and impact. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11(4), 286-292.

[40] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2018). State and local policy levers for increasing treatment and recovery capacity to address the opioid epidemic: Final report. Retrieved from:

[41] Exploring bright spots in Appalachian health: Case studies. Retrieved from: https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/BrightSpotsCaseStudiesJuly2018.pdf.

[42] Exploring bright spots in Appalachian health: Case studies. Retrieved from: https://www.arc.gov/research/researchreportdetails.asp?REPORT_ID=145.

[43] National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2016, January 22). ED-initiated buprenorphine outperforms referral or SBIRT for ED patients with opioid addiction. Retrieved from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2016/01/ed-initiated-buprenorphine-outperforms-referral-or-sbirt-ed-patients-opioid-addiction.

[44] West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources Bureau for Behavioral Health. (2019). West Virginia screening, brief intervention, referral and treatment project (WVSBIRT). Retrieved from: https://dhhr.wv.gov/bhhf/sections/programs/ProgramsPartnerships/AlcoholismandDrugAbuse/Pages/SBIRT.aspx.

[45] National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health. (2017). Lessons learned from rural opioid overdose reversal grant recipients. Retrieved from: https://nosorh.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ROOR-Report-1.pdf.

[46] Walley, A. Y., Ziming, X., Hackman, H. H., Quinn, E., Doe-Simkins, M., Sorensen-Alawad, A. et al. (2013). Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ, 346, f174.

[47] National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health. (2017). Lessons learned from rural opioid overdose reversal grant recipients. Retrieved from: https://nosorh.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ROOR-Report-1.pdf.

[48] Appalachian Substance Abuse Coalition. (2012). Project revive. Retrieved from: http://stopsubstanceabuse.com/2012/revive.html.

[49] Coffin et al., 2016.

[50] Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Naloxone coprescribing guidance. Retrieved from: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2018-12/naloxone-coprescribing-guidance.pdf.

[51] National Institute of Justice. (2018, August 23). Drug courts. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.nij.gov/topics/courts/drug-courts/pages/welcome.aspx.

[52] Creating a culture of health in Appalachia: Exploring bright spots in Appalachian health: Case studies. Retrieved from: https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/BrightSpotsCaseStudiesJuly2018.pdf.

[53] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Syringe services programs (SSPs) developing, implementing, and monitoring program. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/cdc-hiv-developing-ssp.pdf.

[54] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Access to syringe services programs – Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia, 2013-2017. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6718a5.htm?s_cid=mm6718a5_w.

[55] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Syringe exchange programs in North Carolina. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/public-health/north-carolina-safer-syringe-initiative/syringe-exchange-programs-north.

[56] Harm Reduction Coalition. (2019). Rural syringe services program: Kentucky counties. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://harmreduction.org/ruralsyringe/establishing-a-syringe-services-program/establishing-example-ky/#main.

[57] Virginia Department of Health. (2019). Comprehensive harm reduction and syringe services program. Retrieved from: www.vdh.virginia.gov/lenowisco/harm-reduction/.

[58] Gray, J., Hagemeier, N., Brooks, B., & Alamian, A. (2015). Prescription disposal practices: A 2-year ecological study of drug drop box donations in Appalachia. American Journal of Public Health, 105(9), e89–e94. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302689.

[59] Creating a culture of health in Appalachia: Exploring bright spots in Appalachian health: Case studies. Retrieved from: https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/BrightSpotsCaseStudiesJuly2018.pdf.

[60] Drug Enforcement Administration. (2018). DEA national take back day. Retrieved from: https://takebackday.dea.gov/.

[61] Gray, J. A., & Hagemeier, N. E. (2012). Prescription drug abuse and DEA-sanctioned drug take-back events: Characteristics and outcomes in rural Appalachia. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(15), 1186-1187.

[62] Kocherlakota, P. (2014). Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics, 134(2), e547-561.

[63] MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (2019). Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Retrieved October 30, 2018, from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007313.htm.

[64] Brown, J. D., Goodin, A. J., & Talbert, J. C. (2018). Rural and Appalachian disparities in neonatal abstinence syndrome incidence and access to opioid abuse treatment: Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Rural disparities. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 6–13.

[65] Ko, J. Y., Wolicki, S., Barfield, W. D., Patrick, S. W., Broussard, C. S., & Yonkers, K. A., et al. (2017). CDC grand rounds: Public health strategies to prevent neonatal abstinence syndrome. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(9), 242.

[66] Bassuk et al., 2016; Gagne et al., 2018.

[67] Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Use Services. (n.d.). Lifeline peer project. Retrieved from: https://www.tn.gov/behavioral-health/substance-abuse-services/prevention/prevention/lifeline-peer-project.html.

[68] CASA-Trinity. (2019). Tioga county. Retrieved February 22, 2019, from: https://www.casa-trinity.org/prevention.php?Coalitions-HCTC-Tioga-County-13.